SUBJECT TREATMENT

Finding a slightly different emphasis or viewpoint to get the best perspective, can make the subject more commanding than simply settling for a less than interesting first view.

If the subject is what inspired the work, and the artist is motivated to say something about that subject, how it is portrayed is vitally important.

But even if you do not have a great view of the subject to work with, it is still possible to rearrange or add to or subtract from the view you have to make a dramatic composition of the creation that results.

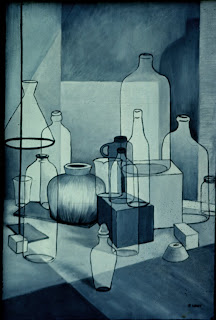

Still Life. Oil on Canvas by R. Wagy

Still Life: Draw, paint or photograph the various objects in a still life grouping. If possible move around to get the best view you can of the grouping. If you can’t move around, or rearrange the still life arrangement, draw the objects in different relationship with each other.

It isn't always required to present the subject realistically. One way to change the way you present the subject is to treat the objects with outline, filling in solid areas.

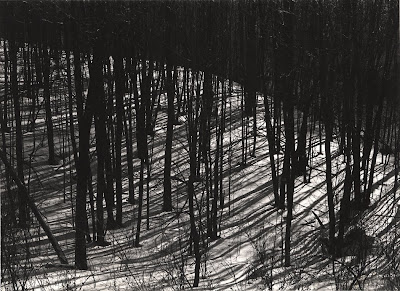

Lighting. Consider side lighting, back lighting or low point lighting to create an unusual view of your subject. At some times of the day, bright illumination creates interesting shadows. The photo at the top of this page illustrates the impact shadows can have at the end or beginning of the day.

Other times the even lighting of an overcast sky is better than unwanted shadows.

Distant or Intimate View?

Consider whether to present the subject from close up or from a distance away. If you are showing off a beautiful costume or capturing an especially interesting expression, probably an intimate view will serve you better.

Think about your choices and what you are trying to say. Choose to place the subject at one side (assymetrically) or centered (symetrically) of your picture plane. With animal or human subjects, do you prefer a direct gaze or averted gaze ? Either may say something about your subject, or this choice may express something about yourself. If your preference is strong, so that you repeatedly present subjects with an averted gaze or a direct gaze, it may be a trait that becomes part of your style.

Images and writing are the property of Ruth Zachary.